Van der Waerden's theorem

Van der Waerden's theorem is a theorem in the branch of mathematics called Ramsey theory. Van der Waerden's theorem states that for any given positive integers r and k, there is some number N such that if the integers {1, 2, ..., N} are colored, each with one of r different colors, then there are at least k integers in arithmetic progression all of the same color. The least such N is the Van der Waerden number W(r, k). It is named after the Dutch mathematician B. L. van der Waerden.[1]

For example, when r = 2, you have two colors, say red and blue. W(2, 3) is bigger than 8, because you can color the integers from {1, ..., 8} like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

B R R B B R R B

and no three integers of the same color form an arithmetic progression. But you can't add a ninth integer to the end without creating such a progression. If you add a red 9, then the red 3, 6, and 9 are in arithmetic progression. Alternatively, if you add a blue 9, then the blue 1, 5, and 9 are in arithmetic progression. In fact, there is no way of coloring 1 through 9 without creating such a progression. Therefore, W(2, 3) is 9.

It is an open problem to determine the values of W(r, k) for most values of r and k. The proof of the theorem provides only an upper bound. For the case of r = 2 and k = 3, for example, the argument given below shows that it is sufficient to color the integers {1, ..., 325} with two colors to guarantee there will be a single-colored arithmetic progression of length 3. But in fact, the bound of 325 is very loose; the minimum required number of integers is only 9. Any coloring of the integers {1, ..., 9} will have three evenly spaced integers of one color.

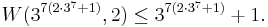

For r = 3 and k = 3, the bound given by the theorem is 7(2·37 + 1)(2·37·(2·37 + 1) + 1), or approximately 4.22·1014616. But actually, you don't need that many integers to guarantee a single-colored progression of length 3; you only need 27. (And it is possible to color {1, ..., 26} with three colors so that there is no single-colored arithmetic progression of length 3; for example, RRYYRRYBYBBRBRRYRYYBRBBYBY.)

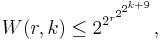

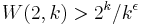

Anyone who can reduce the general upper bound to any 'reasonable' function can win a large cash prize. Ronald Graham has offered a prize of US$1000 for showing W(2,k)<2k2.[2] The current record is due to Timothy Gowers,[3] who establishes

by first establishing a similar result for Szemerédi's theorem, which is a stronger version of Van der Waerden's theorem. The previously best known bound was due to Saharon Shelah and proceeded via first proving a result for the Hales–Jewett theorem, which is another strengthening of Van der Waerden's theorem.

The best-known lower bound for  is that

is that  for all positive ε.[4]

for all positive ε.[4]

Contents |

Proof of Van der Waerden's theorem (in a special case)

The following proof is due to Ron Graham and B.L. Rothschild.[5] Khinchin[6] gives a fairly simple proof of the theorem without estimating W(r, k).

We will prove the special case mentioned above, that W(2, 3) ≤ 325. Let c(n) be a coloring of the integers {1, ..., 325}. We will find three elements of {1, ..., 325} in arithmetic progression that are the same color.

Divide {1, ..., 325} into the 65 blocks {1, ..., 5}, {6, ..., 10}, ... {321, ..., 325}, thus each block is of the form {b ·5 + 1, ..., b ·5 + 5} for some b in {0, ..., 64}. Since each integer is colored either red or blue, each block is colored in one of 32 different ways. By the pigeonhole principle, there are two blocks among the first 33 blocks that are colored identically. That is, there are two integers b1 and b2, both in {0,...,32}, such that

- c(b1·5 + k) = c(b2·5 + k)

for all k in {1, ..., 5}. Among the three integers b1·5 + 1, b1·5 + 2, b1·5 + 3, there must be at least two that are the same color. (The pigeonhole principle again.) Call these b1·5 + a1 and b1·5 + a2, where the ai are in {1,2,3} and a1 < a2. Suppose (without loss of generality) that these two integers are both red. (If they are both blue, just exchange 'red' and 'blue' in what follows.)

Let a3 = 2·a2 − a1. If b1·5 + a3 is red, then we have found our arithmetic progression: b1·5 + ai are all red.

Otherwise, b1·5 + a3 is blue. Since a3 ≤ 5, b1·5 + a3 is in the b1 block, and since the b2 block is colored identically, b2·5 + a3 is also blue.

Now let b3 = 2·b2 − b1. Then b3 ≤ 64. Consider the integer b3·5 + a3, which must be ≤ 325. What color is it?

If it is red, then b1·5 + a1, b2·5 + a2, and b3·5 + a3 form a red arithmetic progression. But if it is blue, then b1·5 + a3, b2·5 + a3, and b3·5 + a3 form a blue arithmetic progression. Either way, we are done.

A similar argument can be advanced to show that V(3, 3) ≤ 7(2·37+1)(2·37·(2·37+1)+1). One begins by dividing the integers into 2·37·(2·37 + 1) + 1 groups of 7(2·37 + 1) integers each; of the first 37·(2·37 + 1) + 1 groups, two must be colored identically.

Divide each of these two groups into 2·37+1 subgroups of 7 integers each; of the first 37 + 1 subgroups in each group, two of the subgroups must be colored identically. Within each of these identical subgroups, two of the first four integers must be the same color, say red; this implies either a red progression or an element of a different color, say blue, in the same subgroup.

Since we have two identically-colored subgroups, there is a third subgroup, still in the same group that contains an element which, if either red or blue, would complete a red or blue progression, by a construction analogous to the one for W(2, 3). Suppose that this element is yellow. Since there is a group that is colored identically, it must contain copies of the red, blue, and yellow elements we have identified; we can now find a pair of red elements, a pair of blue elements, and a pair of yellow elements that 'focus' on the same integer, so that whatever color it is, it must complete a progression.

The proof for W(2, 3) depends essentially on proving that W(32, 2) ≤ 33. We divide the integers {1,...,325} into 65 'blocks', each of which can be colored in 32 different ways, and then show that two blocks of the first 33 must be the same color, and there is a block coloured the opposite way. Similarly, the proof for W(3, 3) depends on proving that

By a double induction on the number of colors and the length of the progression, the theorem is proved in general.

Proof

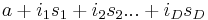

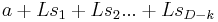

A D-dimensional arithmetic progression consists of numbers of the form:

where a is the basepoint, the s's are the different step-sizes, and the i's range from 0 to L-1. A d-dimensional AP is homogenous for some coloring when it is all the same color.

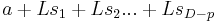

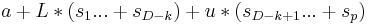

A D-dimensional arithmetic progression with benefits is all numbers of the form above, but where you add on some of the "boundary" of the arithmetic progression, i.e. some of the indices i's can be equal to L. The sides you tack on are ones where the first k i's are equal to L, and the remaining i's are less than L.

The boundaries of a D-dimensional AP with benefits are these additional arithmetic progressions of dimension d-1,d-2,d-3,d-4, down to 0. The 0 dimensional arithmetic progression is the single point at index value (L,L,L,L...,L). A D-dimensional AP with benefits is homogenous when each of the boundaries are individually homogenous, but different boundaries do not have to necessarily have the same color.

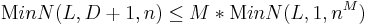

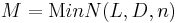

Next define the quantity MinN(L, D, N) to be the least integer so that any assignment of N colors to an interval of length MinN or more necessarily contains a homogenous D-dimensional arithmetical progression with benefits.

The goal is to bound the size of MinN. Note that MinN(L,1,N) is an upper bound for Van-Der-Waerden's number. There are two inductions steps, as follows:

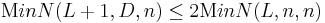

1. Assume MinN is known for a given lengths L for all dimensions of arithmetic progressions with benefits up to D. This formula gives a bound on MinN when you increase the dimension to D+1:

let

Proof: First, if you have an n-coloring of the interval 1...I, you can define a block coloring of k-size blocks. Just consider each sequence of k colors in each k block to define a unique color. Call this k-blocking an n-coloring. k-blocking an n coloring of length l produces an n^k coloring of length l/k.

So given a n-coloring of an interval I of size M*MinN(L,1,n^M)) you can M-block it into an n^M coloring of length MinN(L,1,n^M). But that means, by the definition of MinN, that you can find a 1-dimensional arithmetic sequence (with benefits) of length L in the block coloring, which is a sequence of blocks equally spaced, which are all the same block-color, i.e. you have a bunch of blocks of length M in the original sequence, which are equally spaced, which have exactly the same sequence of colors inside.

Now, by the definition of M, you can find a d-dimensional arithmetic sequence with benefits in any one of these blocks, and since all of the blocks have the same sequence of colors, the same d-dimensional AP with benefits appears in all of the blocks, just by translating it from block to block. This is the definition of a d+1 dimensional arithmetic progression, so you have a homogenous d+1 dimensional AP. The new stride parameter s_{D+1} is defined to be the distance between the blocks.

But you need benefits. The boundaries you get now are all old boundaries, plus their translations into identically colored blocks, because i_{D+1} is always less than L. The only boundary which is not like this is the 0 dimensional point when  . This is a single point, and is automatically homogenous.

. This is a single point, and is automatically homogenous.

2. Assume MinN is known for one value of L and all possible dimensions D. Then you can bound MinN for length L+1.

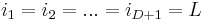

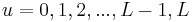

proof: Given an n-coloring of an interval of size MinN(L,n,n), by definition, you can find an arithmetic sequence with benefits of dimension n of length L. But now, the number of "benefit" boundaries is equal to the number of colors, so one of the homogenous boundaries, say of dimension k, has to have the same color as another one of the homogenous benefit boundaries, say the one of dimension p<k. This allows a length L+1 arithmetic sequence (of dimension 1) to be constructed, by going along a line inside the k-dimensional boundary which ends right on the p-dimensional boundary, and including the terminal point in the p-dimensional boundary. In formulas:

if

-

has the same color as

has the same color as

then

-

have the same color

have the same color i.e. u makes a sequence of length L+1.

i.e. u makes a sequence of length L+1.

This constructs a sequence of dimension 1, and the "benefits" are automatic, just add on another point of whatever color. To include this boundary point, one has to make the interval longer by the maximum possible value of the stride, which is certainly less than the interval size. So doubling the interval size will definitely work, and this is the reason for the factor of two. This completes the induction on L.

Base case: MinN(1,d,n)=1, i.e. if you want a length 1 homogenous d-dimensional arithmetic sequence, with or without benefits, you have nothing to do. So this forms the base of the induction. The VanDerWaerden theorem itself is the assertion that MinN(L,1,N) is finite, and it follows from the base case and the induction steps.[5]

See also

- Van der Waerden numbers for all known values for W(n,r) and the best-known bounds for unknown values

References

- ^ van der Waerden, B. L. (1927). "Beweis einer Baudetschen Vermutung". Nieuw. Arch. Wisk. 15: 212–216.

- ^ Graham, Ron (2007). "Some of My Favorite Problems in Ramsey Theory". INTEGERS (The Electronic Journal of Combinatorial Number Theory 7 (2): #A2. http://www.integers-ejcnt.org/vol7-2.html.

- ^ Gowers, Timothy (2001). "A new proof of Szemerédi's theorem". Geom. Funct. Anal. 11 (3): 465–588. doi:10.1007/s00039-001-0332-9. http://www.dpmms.cam.ac.uk/~wtg10/papers.html.

- ^ Brown, Tom C. (2006). "A partition of the non-negative integers, with applications to Ramsey theory". In M. Sethumadhavan. Discrete Mathematics And Its Applications. Alpha Science Int'l Ltd.. pp. 80. ISBN 8173197318.

- ^ a b Graham, R. L.; Rothschild, B. L. (1974). "A short proof of van der Waerden's theorem on arithmetic progressions". Proc. American Math. Soc. 42 (2): 385–386. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1974-0329917-8.

- ^ Khinchin, A. Ya. (1998). Three Pearls of Number Theory. Mineola, NY: Dover. ISBN 978-0486400266.